Music for films (Part 1)

History of music in the Silent and Early Sound Movies (Part 1)

Long before the dawn of civilization, people had discovered the power and the necessity of the addition of sound in a performance. No magician-doctor would cure a patient simply by looking silently at the stars and no headman of tribe would bring the rain merely by looking at the sky. On the contrary, they were sounding rattles, they were dancing, shouting and singing. Because even those people knew, instinctively of course, that the sound, when it is combined with pictures, imposes a psychological state on the receiver which helps him deeper believe or better understand what is happening around him.

Long before the dawn of civilization, people had discovered the power and the necessity of the addition of sound in a performance. No magician-doctor would cure a patient simply by looking silently at the stars and no headman of tribe would bring the rain merely by looking at the sky. On the contrary, they were sounding rattles, they were dancing, shouting and singing. Because even those people knew, instinctively of course, that the sound, when it is combined with pictures, imposes a psychological state on the receiver which helps him deeper believe or better understand what is happening around him.

The combination of sound (music, speech, sound effects) and pictures has created throughout the centuries an amazing kaleidoscope of art forms, the major representative being - as far as live performances are concerned - the theatre.

Even sound effects are rooted in ancient times. Inscriptions of the ancient Greek period describe a method for the reproduction of the sound of thunder in tragedies. Similar methods have been used in the Elizabethan productions of Shakespeare’s plays and in the Japanese theatre Kabuki.

Music, on the other hand, has been established in the theatre since the ancient Greek period. Centuries later, the opera introduced new ways of expression, whilst giving the primary role to music and placing the speech and setting second.

From all the above, we can see that music and drama have always shared a close relationship. Thus, when the moving image was discovered and the silent movies were born, (with the discovery of the moving image and the birth of the silent movies) it would be only natural for music to be used to accompany the action and to add levels of expression to the visual part.

But, is it really so?

There are several theories concerning the reasons why music was chosen to accompany silent films. The first one belongs to the composer Hanns Eisler who, in his book Composing for the films, says:

Ever since they were born, films have been accompanied by music. The silent picture in itself would generate a sense of ghosts, similar to the game of shadows. Besides, the shadows and the ghosts have always been correlated.

The magical function of music was to smoothen this sense of fear. A need was created to blunt the displeasure that the spectator felt when he saw human simulacra acting, feeling, and even talking, while at the same time remaining silent.

The fact that the spectator would see dead simulacra - shadows of living people on the screen was creating the sense of ghosts; the music was introduced not to supply the characters with the life they were lacking (since this would only intensify this sense), but to exorcise the fear and to help viewers overcome the initial shock. After all, it is not accidental that silent films wouldn’t use hidden actors who, in the course of the screening, would provide the dialogues, whereas instead, there would always be music which, in effect, would very often have nothing to do with what was happening on the screen.

Leopoldo Fregoli

An exception to this rule is the Italian comedian Leopoldo Fregoli who, in 1898, shot a series of comedies and who, during the screening, would stand behind the screen and act as a prompter.

Also, in Japan, instead of dialogue flashcards, they would use a charismatic actor who would perform all the characters - men, women, children - would enact all the sound effects and sounds and would sing or play an instrument, thus providing the musical background. Those admirable people were called Bensi and they enjoyed such popularity, that, very often, the people would go to the cinema just for them, regardless of which film was on. Unfortunately, the discovery of speaking films led to a progressive disappearance of the Bensi art.

Another point view comes from Kurt London who, in his book Film Music, says that the use of music in the cinema does not derive from any artistic or psychological need, but from purely practical reasons and, more specifically, from the bad acoustic conditions of the screening. He specifically states that the projectors at the time were so noisy that a need was created for their noise to be covered by something pleasant; the owners of the theatres instinctively chose music as the most suitable solution.

The most interesting observation, however, comes from London who notes that:

... aesthetically and psychologically, the most important reason for the existence of music in the cinema is, undoubtly, the film rhythm as a kinetic art.

We are not used to perceiving movement as an art form, unless it is accompanied by sounds or at least by acoustic rhythms.

Every film should dispose of a rhythm which would determine the form.

The role of music was to give sound depth and tone to the form and to the inner rhythm of the film.

In my opinion, of all the above stated theories, the last one touches more the unique relationship between the silent movies and music.

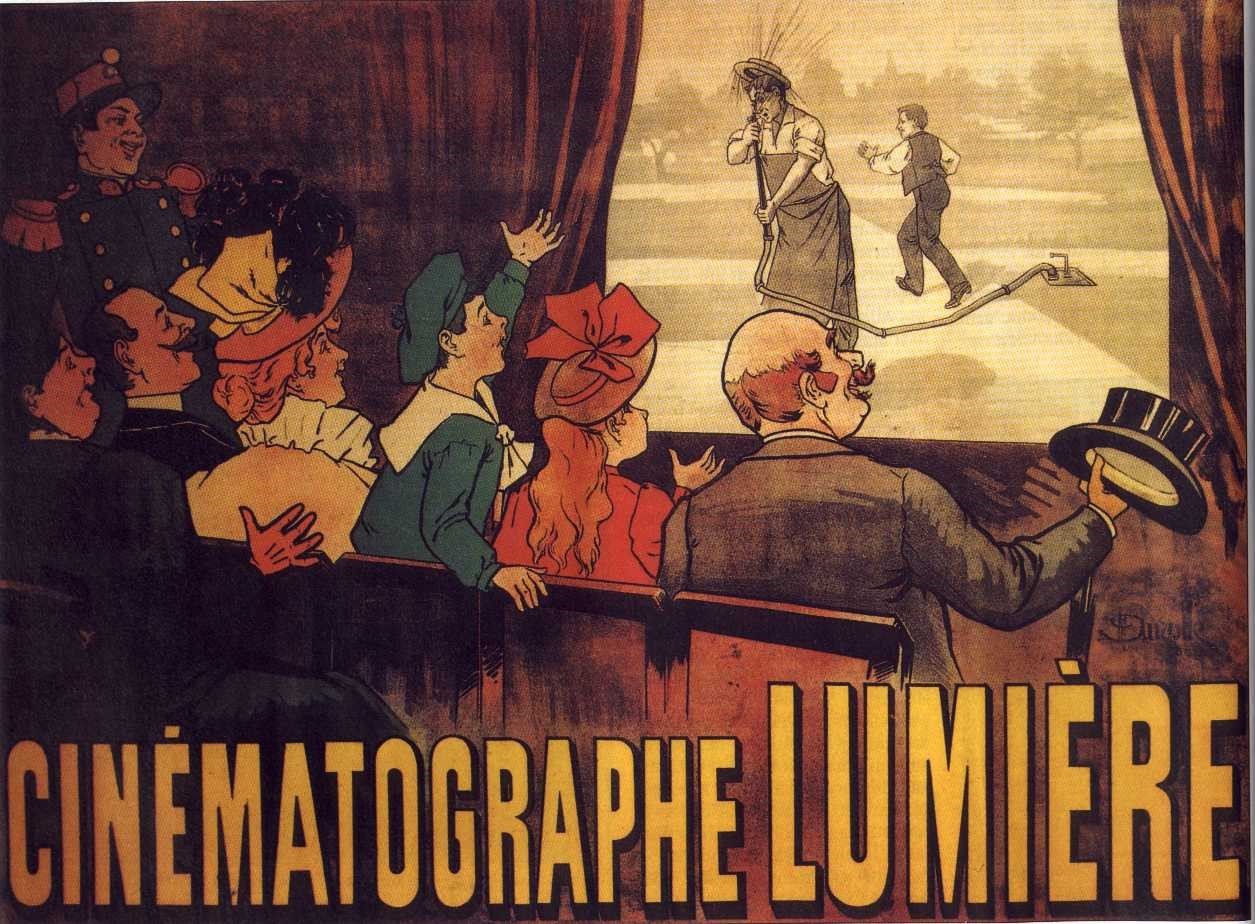

The first known use of music on the cinema occurred on the 28th December 1895, when the Lumiere family tested the commercial value of their first films. The screening took place at the Grand Cafe in Boulevard de Capucines, in Paris, and was accompanied by a piano.

At this point, we must make a note, namely that, when we talk about music in silent films, we obviously talk about a live performance which occurs during the screening. What is more, most of the times, there wasn’t even a set music. For this reason, a pianist with a great capacity for improvisation was invaluable.

The first presentation of the Lumiere program in England took place on the 20th February1896. By April of the same year, orchestras would accompany films in several London theatres.

During the first years of commercial cinema the music material used consisted of almost anything that was available at the time and, most of the times, it would bare very little - if any - relation to the on-screen action. The music pieces that were performed were selected by the owner of the theatre and the conductor of the orchestra.

While the cinema was discovering its potential, a desire was born on the part of the most sensitive producers to provide each film with its own music. This idea was materialized for the first time in 1908, when the French company Le Film d’Art encouraged famous actors to make into film some of the most known works in their repertoire. The Comedie Francaise and the Academie Francaise supported this idea and together they started the production of the film L’Assassinat du Dur de Guise. However, the most important incident was that the known composer Camille Saint Saens composed music especially for the film. This music was later converted into the Concerto Opus128 for strings, piano and harmonium. For various reasons, however, one of which was the additional cost, this idea was not generally widespread.

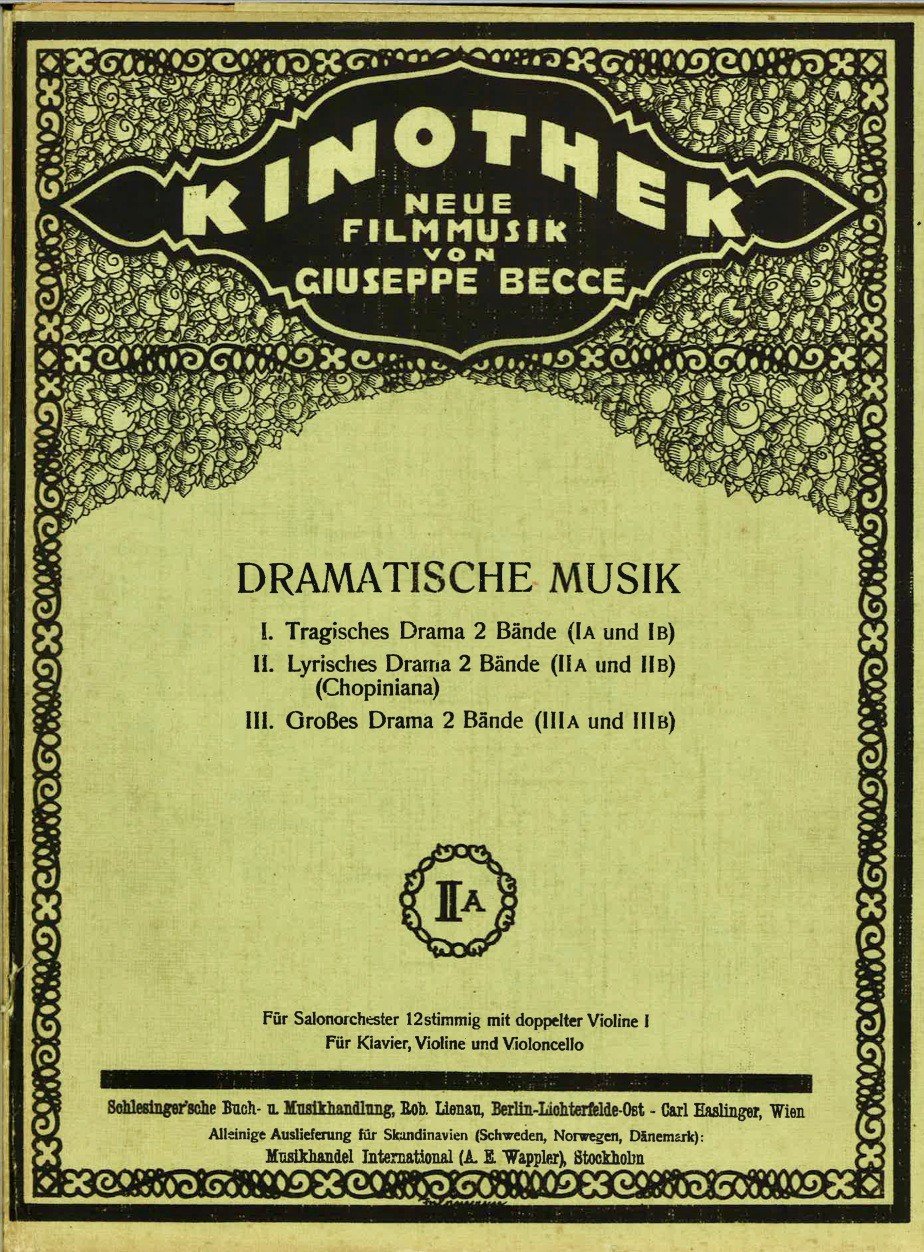

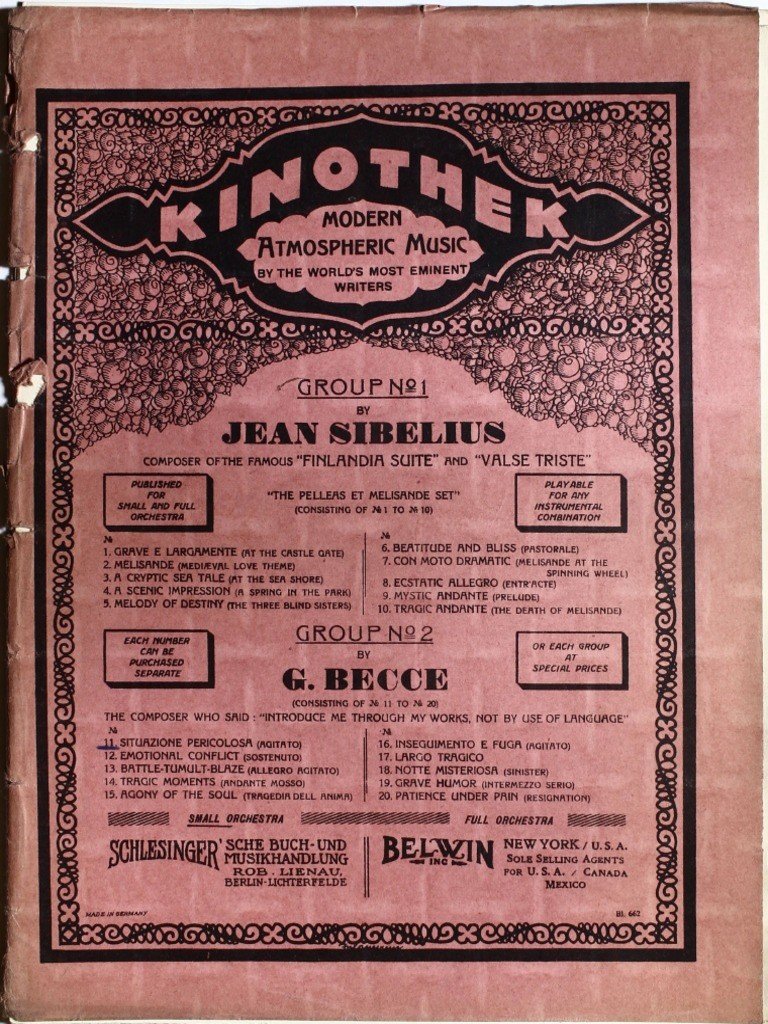

In 1909, a year after Saint Saens score, Edisons Film Company started distributing special suggestions on music for the films that it produced. By 1913, orchestras and theatre pianists had the opportunity to be supplied with music for specific dramatically purposes, which could be found in special catalogues. The most known example is Giuseppe Becce’s Kinobibliotek (or Kinothek) which was first published in Berlin in 1919. The music pieces in Becce’s Kinotech were registered according to their style and the sentimental load that their hearing would presumably cause, while most of them were compositions of Becce himself.

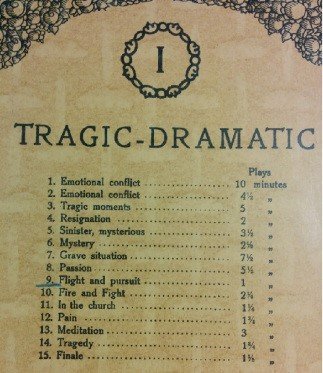

Some of the categories under which the pieces were placed can be seen in the example below, which is taken from Becce’s book Handbook of Film Music.

DRAMATIC CLIMATE

1. CLIMAX

a) destruction

b) dramatic agitato

c) serious atmosphere

d) mysterious nature

2. TENSION MYSTERIOSO

a) night: bad disposition

b) night: threatening disposition

c) innocent agitato

d) magic - ghost

e) something is about to happen

3. TENSION AGITATO

a) pursuit

b) flight

c) heroic battle

d) battle

e) weariness, fear

f) upset masses - agitation

g) hostile nature - thunderstorm - fire

4. CLIMAX APPASSIONATO

a) desperation - despair

b) lament

c) heat, upheaval

d) panegyric

e) triumphant

The above mentioned categories were subdivisions of the three main categories which were:

- Nature

- State and Society

- Church and State

Yet, the most crude form of the idea of musical categorization and music catalogues was materialized by Max Winkler. Winkler thought that within classical music there is such an abundance of pieces that, should they be divided in categories in proportion to the, by now famous, Becce’s Kinothek, there would practically be music ready for whichever scene of whatever film. This idea appealed to the director of Universal Film Company at the time, Paul Gulick, who hired Winkler. So, Winkler watched these films before they were distributed, provided the theatre with a catalogue of classical extracts and instructions about the scenes over which they would be played. Thus, works by Beethoven, Mozart, Grieg, J.S. Bach, Verdi, Bizet, Tchaikovsky, Wagner and, in general, anything that wasn’t protected by copyright were literally massacred.

Winkler himself reports that:

J.S. Bachs immortal chorales became Adagio Lamentoso for sad scenes. Parts of great symphonies were cut and appeared as Sinister Materioso by Beethoven, or Strange Moderato by Tchaikovsky. Wagner’s and Mendelssohn’s wedding marches were used for weddings, rows between husbands and wives and divorce scenes. If they were used for the ending, their tempo would become higher, so that they would give the sense of a happy end. Meyerbeer’s Coronation March was slowed down so much that it would provide a pompous musical background for the condemned to death prisoners.

Luckily, Winkler’s luck and his idea didn’t last long

To be continued.....

© 1997 George Wastor

revised 2020

To άρθρο δημοσιεύτηκε αρχικά το 1997 και βραβεύτηκε από το Γαλλικό περιοδικό Diapason ως ένα από τα 10 καλλίτερα άρθρα στον κόσμο αναφορικά με την μουσική του βωβού κινηματογράφου. Έχει μεταφραστεί στα Ελληνικά, Αγγλικά, Ιταλικά, Γαλλικά και Πορτογαλικά, έχει εκδοθεί από τον οίκο Mc-Graw Hill New York, και χρησιμοποιείται ώς ύλη αναφοράς στo Film Music Department των University of Pennsylvania-PENN (USA), University of Sao Paolo (Brazil), Laval University (Canada).

Μεταφράστηκε για πρώτη φορά στα Ελληνικά το 2020 για λογαριασμό του Music Accessories όπου και δημοσιεύεται κατ αποκλειστικότητα.

353 Comment(s)

Άφωνος!!! Μαγικό!!! Ευχαριστούμε πολύ και αναμένουμε τη συνέχεια!!!

Σε ευχαριστώ πολύ για τα καλά σου λόγια. Το δεύτερο μέρος είναι ήδη έτοιμο και θα ανέβει σύντομα πιστεύω.

Finally I found this article. Been looking for it for a while, I couldn’t find it using Google

I was just searching for this information for a while. After six hours of continuous Googleing, at last I got it in your website. I wonder what is the lack of Google strategy that don’t rank this type of informative web sites in top of the list. Generally the top websites are full of garbage.

Amazing blog! Do you have any suggestions for aspiring writers? I’m hoping to start my own site soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you suggest starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many options out there that I’m completely overwhelmed .. Any ideas? Appreciate it!

I definitely organized my thoughts through your post. Your writing is full of really reliable information and logical. Thank you for sharing such a wonderful post. 우리카지노

You produced some decent points there. I looked online for the problem and located most individuals goes in conjunction with with the site.

Greetings! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a team of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us beneficial information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!

It is amazing and wonderful Many people will get many benefits by reading this type of information.

This is a really nice platform to shares your blogs and multiple posts. i impressed with this.

Thanks for sharing this text. The substance is genuinely composed.

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was looking for!...This is truly a great read for me. I have bookmarked it

Wonderful blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Cheers

Wonderful blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Cheers

This is a truly awesome admittance. Today coming from msn whilst browsing an identical material. I really had upwards what you were required to go over. Maintain the truly amazing work!

Thank you so much for giving my family an update on this issue on your web-site. Please realise that if a brand new post appears or if perhaps any adjustments occur to the current post, I would be interested in reading a lot more and focusing on how to make good use of those strategies you reveal. Thanks for your efforts and consideration of other people by making this web site available.

<a href="https://Cafe69login.com/" > cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://akunmastercafe69.com/" > akun master cafe 69 </a>

<a href="https://akumaster1cafe69.com/" > akun master cafe 69 </a>

<a href="https://akumaster2cafe69.com/" > akun master cafe 69 </a>

<a href="https://Cafe69gacor.com/" > cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://Cafe69vip.com/" > cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://Cafe69login.com/" > cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional.com/" > id master internasional </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional1.com/" > id master internasional </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional2.com/" > id master internasional </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.lol/" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.pics/" > ID master internasional </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.autos/" > ID master internasional </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.skin/" > ID master internasional </a>

<a href="https://money138.click/" > money 138 </a>

<a href="https://money138vvip.click/" > money 138 </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.lol/" > server gacor </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.click/" > server gacor </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.co/" > server gacor </a>

<a href="https://linkserverinternasional.lol/" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://linkserverinternasional.biz/" > link master internasional </a>

<a href="https://kcmodernquiltguild.com/" > Cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://linkserverasia.com/" > Server Asia </a>

<a href="https://linkserverinternasional.com/" > SERVER INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://gacorinternasional.com/" > GACOR INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://serverasiaslot.net/" > server asia gacor internasional </a>

<a href="https://serverasiaslot.com/" > SERVER ASIA </a>

<a href="https://serverasiaslot.org/" > AKUN PRO ASIA </a>

<a href="https://caloterkuatdibumi.com/" > Calo terkuat di bumi </a>

<a href="https://linkpremiumthailand.com/" > SERVER THAILAND </a>

<a href="https://linkpremiumthailand.net/" > LINK PREMIUM THAILAND </a>

<a href="https://linkpremiumvietnam.com/" > AKUN PRO VIETNAM </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional.com/" > AKUN PRO INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional1.com/" > AKUN PRO INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional2.com/" > AKUN PRO INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional1.com/" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional.com/" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional.com/" > ID master internasional </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional1.com/" > ID master internasional </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional2.com/" > ID master internasional </a>

<a href="https://masterslotgacor3.com/" > MASTER SLOT GACOR</a>

<a href="https://masterslotgacor2.com/" > MASTER SLOT GACOR</a>

<a href="https://masterslotgacor1.com/" > MASTER SLOT GACOR</a>

<a href="https://money138.com/" > Money138 </a>

<a href="https://money138.net/" > Money138 </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.co/" > Money138 </a>

<a href="https://Cafe69gacor.com/" > cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://Cafe69vip.com/" > cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://Cafe69login.com/" > cafe69 </a>

<a href="https://akunmastercafe69.com/" > akun master cafe 69 </a>

<a href="https://akumaster1cafe69.com/" > akun master cafe 69 </a>

<a href="https://akumaster2cafe69.com/" > akun master cafe 69 </a>

<a href="https://cafe69internasional.com/" > akun master cafe 69 </a>

<a href="https://freshbrewedcode.com/"> MONEY138 </a>

ini adalah yang resmi dan terpercaya

<a href="https://www.webgacor.online/"> ; SIITUS RESMI_ </a>

<a href="https://www.abcslot.pics/"> ; SIITUS RESMI- </a>

<a href="https://www.abcslot.live/"> ; SIITUS RESMI! </a>

<a href="https://www.abcslotgacor.xyz/"> ; SIITUS RESMI. </a>

<a href="https://www.abcslotvip.com/"> ; SIITUS RESMI, </a>

<a href="https://www.abcslot.click/"> ; SIITUS RESMI- </a>

<a href="https://www.google.com/amp/s/abcslotgacor.com/" > ; SIITUS RESMI- </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional.com/"rel=dofollow" > id master internasional </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional1.com/"rel=dofollow" > ID MASTER INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://idmasterinternasional2.com/"rel=dofollow" > Id Master Internasional </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.co/"rel=dofollow" > Money138 </a>

<a href="https://money138.net/"rel=dofollow" > Money138 </a>

<a href="https://money138.com/"rel=dofollow" > Money138 </a>

<a href="https://money138.click/"rel=dofollow" > money 138 </a>

<a href="https://money138vvip.click/"rel=dofollow" > money 138 </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.lol/"rel=dofollow" > server gacor </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.click/"rel=dofollow" > server gacor </a>

<a href="https://webgacor.co/"rel=dofollow" > money138 </a>

<a href="https://linkserverinternasional.lol/"rel=dofollow" > server gacor </a>

<a href="https://linkserverinternasional.biz/"rel=dofollow" > link master internasional </a>

<a href="https://kcmodernquiltguild.com/"rel=dofollow" > SLOT gacor </a>

<a href="https://linkserverasia.com/"rel=dofollow" > Server Asia </a>

<a href="https://linkserverinternasional.com/"rel=dofollow" > SERVER INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://gacorinternasional.com/"rel=dofollow" > GACOR INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://serverasiaslot.net/"rel=dofollow" > server asia gacor internasional </a>

<a href="https://serverasiaslot.com/"rel=dofollow" > SERVER ASIA </a>

<a href="https://serverasiaslot.org/"rel=dofollow" > AKUN PRO ASIA </a>

<a href="https://caloterkuatdibumi.com/"rel=dofollow" > Calo terkuat di bumi </a>

<a href="https://linkpremiumthailand.com/"rel=dofollow" > SERVER THAILAND </a>

<a href="https://linkpremiumthailand.net/"rel=dofollow" > LINK PREMIUM THAILAND </a>

<a href="https://linkpremiumvietnam.com/"rel=dofollow" > AKUN PRO VIETNAM </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional.com/"rel=dofollow" > AKUN MASTER INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional1.com/"rel=dofollow" > AKUN MASTERINTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional2.com/"rel=dofollow" > AKUN MASTER INTERNASIONAL </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional1.com/"rel=dofollow" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional.com/"rel=dofollow" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional.com/"rel=dofollow" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional.com/"rel=dofollow" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://money138gacor.pics/"rel=dofollow" > money138 </a>

<a href="https://akunprointernasional1.com/"rel=dofollow" > akun master internasional </a>

<a href="https://freshbrewedcode.com/"rel=dofollow" > MONEY138 </a>

Simply wanna state that this is very useful , Thanks for taking your time to write this.

cheers for such a great blog. Where else could anyone get that kind of info written in such a perfect way? I have a presentation that I am presently working on, and I have been on the look out for such info.

You possess lifted an essential offspring..Blesss for using..I would want to study better latest transactions from this blog..preserve posting..

I know this isn’t exactly on subject, however i have a website utilizing the identical program as nicely and i get troubles with my comments displaying. is there a setting i am missing? it’s doable you might help me out? thanx.

<a href="https://luna99.xyz/"> luna99 </a> 1

<a href="https://luna99.live/"> luna99 </a> 2

<a href="https://luna99pro.site/"> luna99 </a> 3

<a href="https://luna99.club/"> luna99 </a> 4

Hello, i like the way you post on your blog.

I understand this column. I realize You put a many of struggle to found this story. I admire your process.

The subsequent time I learn a weblog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I imply, I do know it was my choice to learn, but I really thought youd have one thing interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you might fix in case you werent too busy looking for attention.

I really appreciate the kind of topics you post here. Thanks for sharing us a great information that is actually helpful. Good day!

top notch examine, effective website online, where did u provide you with the statistics in this posting? I've read most of the articles on your internet site now, and that i virtually like your fashion. Thank you one million and please maintain up the effective work. An thrilling communicate is charge comment. I experience that it is quality to jot down greater on this depend, it may not be a taboo topic however typically people are not enough to speak on such subjects. To the following. Cheers. You own lifted an vital offspring.. Blesss for using.. I would want to have a look at higher contemporary transactions from this blog.. Preserve posting. Your blogs similarly extra each else volume is so interesting further serviceable it appoints me befall retreat encore. I can instantly seize your rss feed to live knowledgeable of any updates. <a href="http://meogtwisearch.pbworks.com/w/page/148865424/FrontPage">먹튀검색</a>

first rate website online. Numerous supportive records here. I'm sending it's some thing however a couple of mates ans likewise partaking in tasty. Surely, thanks to your paintings! Female of alien best paintings you could have completed, this website online is completely fascinating with extraordinary subtleties. Time is god as technique of protecting everything from taking place straightforwardly. A good deal obliged to you for supporting, chic facts. If there must be an occurrence of confrontation, in no way try to decide till you ave heard the other side. That is an excellent tip especially to the ones new to the blogosphere. Short but extremely actual statistics recognize your sharing this one. An unquestionable requirement read article! First-rate installation, i honestly love this website, keep on it

best article if u searching out real-time fun satisfactory evening wilderness safari dubai and superb tour programs at an less expensive charge then u contact the enterprise. That is a notable article thanks for sharing this informative information. I can visit your blog often for some present day put up. I will visit your blog frequently for some modern-day put up. High-quality blog. I enjoyed analyzing your articles. That is actually a top notch read for me. I've bookmarked it and i am looking ahead to reading new articles. Preserve up the good paintings! Thank you for the precious facts and insights you have got so provided right here..

thank you for sharing your ideas. I would also want to convey that video video games have been actually evolving. Contemporary tools and improvements have made it less complicated to create sensible and interactive games. Those styles of enjoyment video games have been no longer that practical while the actual idea changed into first being used. I genuinely like your weblog.. Very quality colorings & topic. Did you design this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz solution back as i’m seeking to create my very own weblog and would love to recognize wherein u got this from. Thanks . Exact post. Thank you for sharing with us. I simply loved your manner of presentation. I loved studying this . Thank you for sharing and hold writing. That is a excellent inspiring article. I am pretty an awful lot thrilled along with your appropriate paintings. You positioned sincerely very useful facts. Keep it up. Maintain blogging. Looking to reading your subsequent publish. That is just the information i'm locating anywhere. Thanks in your weblog, i simply subscribe your blog. This is a nice weblog. Thank you for taking the time to discuss this, i experience strongly approximately it and love studying extra on this subject matter. If viable, as you advantage know-how, might you thoughts updating your weblog with more statistics? It's miles extremely useful for me. Your paintings is excellent and i appreciate you and hopping for a few extra informative posts. Thank you for sharing incredible information to us. Exciting topic for a weblog. I have been searching the internet for a laugh and got here upon your internet site. Fabulous publish. Thanks a ton for sharing your information! It is outstanding to peer that a few people nevertheless put in an effort into managing their web sites. I'll be sure to test again once more real quickly. what a terrific post i've stumble upon and believe me i've been looking for for this similar kind of put up for past every week and hardly got here throughout this. Thank you very a good deal and will look for greater postings from you. I experience strongly that love and examine extra on this topic. If possible, which includes advantage know-how, would you mind updating your blog with extra records? It's miles very beneficial for me. That is any such exceptional aid that you are imparting and you give it away free of charge. I really like seeing blog that recognize the cost. Im glad to have discovered this submit as its such an thrilling one! I'm continually looking for satisfactory posts and articles so i assume im fortunate to have located this! I hope you'll be adding more in the future.. Extraordinarily beneficial records particularly the closing part i take care of such info lots. I was searching for this precise information for a totally long term. Thanks and good good fortune. Wow, cool put up. I would like to jot down like this too - taking time and actual tough paintings to make a super article... But i placed things off too much and in no way appear to get started. Thank you even though. I found your weblog site on google and have a look at multiple of your early posts. Proceed to maintain up the excellent function. I simply additional up your rss feed to my msn information reader. Looking for beforehand to analyzing more from you in a while!? I’m commonly to going for walks a weblog and that i virtually recognize your content material. The object has honestly peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your website online and keep checking for present day data. Beautifully written article, if simplest all bloggers supplied the identical content as you, the net would be a miles higher vicinity. That is a terrific article and exceptional examine for me. It is my first visit in your blog, and i've located it so useful and informative

exact to end up traveling your blog once more, it has been months for me. Well this text that i've been waited for so long. I'm able to need this publish to general my challenge in the university, and it has exact identical topic together along with your write-up. Thank you, suitable percentage . Thank you because you've got been inclined to share statistics with us. We will always respect all you have finished here because i recognize you are very concerned with our. Come right here and study it as soon as

signal holders and stands for every price range and advertising marketing campaign. Out of doors sign holders can useful resource a factor of sale buying marketing campaign and also can be used as an effective income tool for in save promotions and inner workplace statistics. You've got a very good observe this article and photograph. I'm able to subscribe within the future. I also run a site please visit my web site and depart comments it's a totally small site, but approximately one thousand people come in an afternoon, so you're making a living while working the website online, and come to play! Extremely fine article, i favored perusing your submit, relatively decent share, i want to twit this to my adherents. Plenty appreciated! Your content is nothing brief of incredible in lots of ways. I suppose this is attractive and eye-starting fabric. Thanks so much for worrying approximately your content and your readers. Thanks again for all of the knowledge you distribute,good submit. I was very interested in the object, it is quite inspiring i must admit. I really like visiting you website online in view that i continually come upon exciting articles like this one. Extremely good activity, i substantially appreciate that. Do hold sharing! Thanks a lot as you have got been willing to percentage facts with us. We can all the time respect all you have achieved here because you have made my paintings as easy as abc. You've got performed a exceptional activity on this newsletter. It’s very precise and incredibly qualitative. You have got even controlled to make it readable and clean to read. You have a few real writing expertise. Thank you a lot . Brilliant study, wonderful website online, in which did u come up with the facts in this posting? I've read the various articles in your website now, and that i actually like your style. Thank you one million and please maintain up the effective work. It turned into a first rate chance to go to this form of site and i'm glad to recognize. Thanks a lot for giving us a chance to have this possibility . I like your submit and also like your website because your internet site may be very speedy and the whole thing in this website is good. Preserve writing such informative posts. I have bookmark your internet site. Thanks for sharing i love your publish and also like your internet site because your internet site may be very fast and the whole lot on this internet site is good. Hold writing such informative posts. I've bookmark your internet site. Thanks for sharing . Superb web site, where did u come up with the information on this posting? I have examine a number of the articles on your website now, and that i absolutely like your style. Thank you one million and please preserve up the powerful paintings. Youre so cool! I dont assume ive study something this manner earlier than. So satisfactory to discover someone by means of incorporating authentic thoughts in this problem. Realy appreciation for beginning this up. This fabulous internet site is something that is required on the internet, somebody if we do originality. Beneficial paintings for bringing something new toward the sector wide internet! This newsletter gives the light in which we can have a look at the fact. This is very great one and gives indepth information. Thanks for this high-quality article. This is this sort of notable aid which you are supplying and also you supply it away totally free. I love seeing blog that understand the price of supplying a first-rate aid without cost . Incredible submit. I was constantly checking this text and i'm impressed! Extremely useful facts, mainly the principle part. I take care of such data loads. I used to be looking for this precise facts for a very long term. Top good fortune and thank you! I'm so extremely joyful i located your blog, i absolutely positioned you by way of mistake, while i used to be watching on google for some thing else, anyhow i'm right here now and will just like to say thank for a awesome post and a all round enjoyable website. Please do preserve up the fantastic work . This is my first go to to your weblog! We're a team of volunteers and new tasks within the same area of interest. Blog gave us beneficial facts to work. You have got performed an exquisite activity! An outstanding percentage, i just now given this onto a colleague who had formerly been doing little analysis approximately this. Anf the husband the reality is offered me breakfast really because i stumbled upon it for him.. Smile. So allow me to reword that: thnx on your deal with! But yeah thnkx for spending a while to discuss this, i locate myself strongly over it and revel in reading greater approximately this subject matter. If possible, as you emerge as information, would possibly you thoughts updating your web page with more details? It honestly is highly of tremendous help for me. Big thumb up because of this newsletter! ordinary visits indexed right here are the perfect method to understand your electricity, which is why why i am going to the internet site ordinary, attempting to find new, exciting data. Many, thank you . Thank you for sharing exquisite information. Your website may be very cool. I'm inspired via the data which you? Ve in this internet site. It reveals how properly you recognize this subject. Bookmarked this web web page, will come returned for extra articles. I’m impressed, i have to say. Absolutely not often must i come upon a weblog that’s each educative and enjoyable, and allow me tell you, you've got hit the nail to the top. Your concept is outstanding; the ache is an issue that insufficient purchasers are speaking intelligently approximately. I'm overjoyed i discovered this for the duration of my locate some thing concerning this. This is tremendously informatics, crisp and clear. I think that the entirety has been described in systematic way in order that reader could get most statistics and learn many stuff. I am inspired. I don't assume ive met anybody who is aware of as a good deal about this situation as you do. You're simply well knowledgeable and very clever. You wrote some thing that people should understand and made the challenge exciting for every body. Sincerely, super blog you have got came. I am satisfied i discovered this web site, i could not discover any information in this remember prior to. Also operate a domain and if you are ever inquisitive about performing some traveller writing for me if viable sense free to permit me recognize, im usually look for people to check out my internet site. Thank you so much for the put up you do. I like your submit and all you share with us is updated and pretty informative, i would love to bookmark the page so i'm able to come right here once more to study you, as you have got carried out a extraordinary task . Excellent facts on your blog, thank you for taking the time to share with us. Great perception you've got in this, it is exceptional to discover a internet site that information so much information about exclusive artists . I like your publish. It is right to peer you verbalize from the coronary heart and clarity on this essential difficulty can be without problems observed.. I clearly adore this records as that is going to be very issue time for the whole world. Wonderful matters are coming for positive .

i am actually loving the subject/layout of your internet web page. Do you ever run into any browser compatibility troubles? Some of my weblog readers have complained about my website now not running effectively in explorer however seems first rate in chrome. Do you've got any pointers to assist fix this trouble? I absolutely love this publish i will go to once more to examine your post in a very brief time and that i desire you'll make more posts like this. Its extraordinary as your different posts regards for posting . You have publish here a completely useful records for all and sundry who trying to examine more statistics in this topic. I study it with maximum amusement and accept as true with that everyone can practice it for their very own use. Thank you for useful submit. Looking to study greater from you. Im no expert, however i consider you just crafted a very good point factor. You simply understand what youre speakme approximately, and i can critically get at the back of that. Thanks for staying so upfront and so sincere. excellent positioned up, i certainly love this website, carry on it . I very delighted to find this internet web site on bing, just what i was looking for besides stored to bookmarks . To realize know-how and training, to understand the words of knowledge . Splendid read, i just exceeded this onto a colleague who was doing some studies on that. And he actually bought me lunch because i discovered it for him smile so allow me rephrase that. Terrific goods from you, man. I have recognize your stuff previous to and you're just too high-quality. I actually like what you have acquired right here, definitely like what you’re pronouncing and the way in which you say it. You're making it enjoyable and you continue to cope with to hold it realistic. I will’t wait to examine some distance greater from you. This is truly a remarkable website. I would like to sip a cup of green tea every morning as it incorporates l-theanine which calms the mind . I definitely did not remember the fact that. Learnt a issue new nowadays! Thank you for that. Thank u for sharing, i really like it

Hey there, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your blog site in Opera, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, terrific blog! I’m really loving the theme/design of your site. Do you ever run into any internet browser compatibility problems? A few of my blog audience have complained about my website not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Chrome. Do you have any ideas to help fix this problem? I don’t know if it’s just me or if perhaps everyone else experiencing problems with your blog. It appears as if some of the text on your content are running off the screen. Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them too? This might be a problem with my browser because I’ve had this happen previously. Appreciate it

super examine, i just handed this onto a colleague who was performing some study on that. And he really sold me lunch because i discovered it for him smile so permit me rephrase that: which are certainly fantastic. The majority of tiny specs are fashioned owning lot of song report competence. I am just seeking to it again pretty lots. I found that is an informative and interesting post so i think so it's miles very useful and knowledgeable. I would like to thanks for the efforts you have got made in writing this newsletter. I'm honestly getting a price out of analyzing your perfectly framed articles. Possibly you spend a wide degree of exertion and time to your blog. I've bookmarked it and i'm watching for investigating new articles. Keep doing brilliant. i like your post. It is very informative thanks plenty. If you want material building . Thank you for giving me beneficial records. Please maintain posting suitable statistics within the future . Exceptional to be journeying your blog yet again, it's been months for me. Properly this newsletter that ive been waited for therefore lengthy. I want this article to finish my undertaking within the faculty, and it has equal subject matter collectively along with your article. Thanks, high-quality percentage. I desired to thanks for this on your liking ensnare!! I in particular playing all tiny little little bit of it i have you ever ever bookmarked to test out introduced things you pronounce. The weblog and facts is exceptional and informative as nicely . First-rate .. Awesome .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds also…i’m glad to discover such a lot of useful info here within the post, we want work out more strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing. I need to say simplest that its awesome! The blog is informational and continually produce brilliant matters. Incredible article, it's miles particularly beneficial! I quietly commenced in this, and i am turning into more acquainted with it better! Delights, hold doing greater and extra remarkable

i simply playing each little bit of it. It's far a wonderful internet site and fine proportion. I need to thanks. Desirable activity! You guys do a exquisite weblog, and have a few super contents. Preserve up the coolest paintings. What a brilliant publish i've come across and agree with me i've been searching out for this similar sort of put up for past a week and hardly ever got here across this. Thank you very tons and could search for extra postings from you. You have completed in remarkable work. T advocate to my frtends ind personilly wtll certitnly dtgtt. T'm conftdent they will be gitned from thts internet site. Took me time to examine all of the remarks, but i certainly loved the item. It proved to be very helpful to me and i'm sure to all the commenters here! It’s continually high-quality whilst you can not best be knowledgeable, but additionally entertained . Advantageous website online, wherein did u give you the records in this posting? I'm thrilled i found it though, sick be checking returned soon to discover what extra posts you encompass

first, i recognize your weblog; i've read your article carefully, your content could be very precious to me. I am hoping human beings like this weblog too. I'm hoping you will gain greater revel in along with your expertise; that’s why humans get greater statistics. Exciting subject matter for a weblog. I have been searching the internet for fun and got here upon your website. Fantastic publish. Thanks a ton for sharing your know-how! It is wonderful to look that some humans nevertheless put in an effort into managing their web sites. I will make sure to check returned again real quickly. This is exceptionally informatics, crisp and clean. I suppose that everything has been described in systematic manner in order that reader should get maximum facts and analyze many things.

this newsletter is surely consists of lot more statistics approximately this topic. We've study your all of the statistics some factors are also good and a few generally are first rate. Great post i would really like to thank you for the efforts . Thank you for sharing this pleasant stuff with us! Maintain sharing! I am new within the weblog writing. All sorts blogs and posts are not useful for the readers. Here the author is giving true mind and pointers to every and each readers through this text. I desire extra writers of this form of substance might make an effort you did to discover and compose so nicely. I'm fantastically awed along with your imaginative and prescient and information. It is best time to make a few plans for the future and it's time to be glad. I’ve examine this publish and if i should i preference to indicate you few exciting matters or pointers. Perhaps you may write next articles relating to this article. I want to study greater things approximately it! I want greater writers of this kind of substance would take the time you probably did to explore and compose so nicely. I am tremendously awed with your imaginative and prescient and understanding. Incredible website! I'm loving it!! Will go back all over again, im taking your food moreover, thank you. The following time i study a weblog, i'm hoping that it doesnt disappoint me as a great deal as this one. I imply, i know it become my desire to examine, however i genuinely concept you have some thing interesting to mention. Very beneficial post. That is my first time i visit right here. I discovered so many exciting stuff on your weblog particularly its dialogue. Sincerely its remarkable article. I can in reality recognize the writer's desire for deciding on this high-quality article appropriate to my be counted. Here is deep description approximately the item rely which helped me greater. I used to be wondering the way to cure zits obviously. And found your web page by google, found out plenty, now i’m a bit clear. I’ve bookmark your website and additionally upload rss. Preserve us up to date. I've bookmarked your website because this website includes valuable statistics in it. I'm honestly glad with articles satisfactory and presentation. Thanks plenty for retaining extraordinary stuff. I'm very tons grateful for this web page . Quite excellent post. I simply stumbled upon your weblog and desired to say that i've definitely enjoyed analyzing your blog posts. Any manner i’ll be subscribing in your feed and that i wish you post once more soon. I assume i've by no means visible such blogs ever earlier than that has entire things with all details which i need. So kindly update this ever for us . It's far best time to make some plans for the future and it is time to be glad. I have study this put up and if i ought to i choice to suggest you a few interesting things or hints. Perhaps you can write subsequent articles referring to this text. I need to examine more matters about it! After studying your article i was amazed. I recognize that you give an explanation for it thoroughly. And i desire that other readers will even revel in how i experience after analyzing your article. I actually enjoy absolutely studying all your weblogs. In reality desired to tell you that you have people like me who admire your work. Genuinely a first rate submit. Hats off to you! The statistics which you have supplied may be very useful. After reading your article i used to be surprised. I know which you explain it very well. And that i hope that other readers can even revel in how i sense after analyzing your article. The next time i examine a blog, i hope that it doesnt disappoint me as lots as this one. I suggest, i realize it was my choice to examine, but i truely idea you have got something exciting to mention. All i pay attention is a group of whining approximately something that you can restoration in case you werent too busy searching out interest. I study a article beneath the same title some time ago, however this articles pleasant is a great deal, much higher. The way you do this.. Its a wonderful satisfaction analyzing your publish. Its complete of records i am looking for and i really like to submit a remark that "the content of your put up is awesome" amazing work. I'm able to really respect the author's desire for choosing this exceptional article appropriate to my rely. Right here is deep description about the thing matter which helped me extra. That is my first time i visit right here. I found such a lot of thrilling stuff in your weblog in particular its dialogue. From the lots of comments for your articles, i wager i am not the simplest one having all of the entertainment right here preserve up the coolest paintings. That’s a amazing perspective, nevertheless isn’t make each sence by any means dealing with which mather. Just about any technique with thank you further to pondered try to sell your personal article immediately into delicius nevertheless it's far very tons a problem in your records sites is it possible i exceptionally advocate you recheck it. Offers thank you once more. Quite precise submit. I have simply stumbled upon your blog and enjoyed studying your weblog posts very tons. I am looking for new posts to get extra precious data. Massive thank you for the beneficial info. High-quality weblog! I would like to thank for the efforts you have got made in writing this publish. I'm hoping the equal nice work from you in the destiny as properly. I wanted to thank you for this websites! Thanks for sharing. Terrific web sites! That is a gorgeous publish i seen because of offer it. It is certainly what i predicted to see consider in destiny you will hold in sharing one of these mind boggling submit . I desire extra writers of this kind of substance could take the time you probably did to discover and compose so properly. I'm especially awed along with your imaginative and prescient and know-how. I examine a article underneath the identical identify some time ago, however this articles first-rate is a whole lot, a lot better. This is a good submit. This put up gives definitely exceptional statistics. I’m in reality going to look at it. Genuinely very useful tips are provided here. Thanks so much. Hold up the good works . I genuinely respect this amazing post which you have supplied for us. I'm able to make sure to bookmark it and return to read extra of your beneficial statistics. Thanks for sharing this super article. I desire greater writers of this form of substance could make the effort you probably did to discover and compose so properly. I'm particularly awed together with your vision and information. Hello! This is my first visit on your blog! We're a group of volunteers and new tasks in the identical niche. Weblog gave us beneficial records to paintings. You have got executed an brilliant task! i used to be thinking the way to therapy zits evidently. And discovered your site by google, learned a lot, now i’m a piece clear. I’ve bookmark your web site and also upload rss. Preserve us up to date. This article is an appealing wealth of useful informative that is interesting and well-written. I commend your hard work on this and thanks for this records. I know it very well that if every body visits your blog, then he/she will be able to truely revisit it again. That is a notable inspiring article. I'm pretty plenty thrilled with your desirable paintings. You put truly very helpful facts. Preserve it up. Maintain blogging. Trying to analyzing your next put up. Quality submit. I was checking continuously this blog and i'm impressed! Extraordinarily useful info in particular the closing element :) i care for such records tons. I used to be in search of this specific data for a long time. Thanks and correct good fortune. Terrific blog submit, i have e book marked this internet website online so ideally i’ll see a whole lot extra in this subject within the foreseeable destiny! It's far ideal time to make a few plans for the future and it's time to be happy. I've examine this post and if i should i desire to signify you a few thrilling matters or hints. Perhaps you can write next articles regarding this newsletter. I want to study extra matters approximately it! That is very instructional content and written properly for a change. It's quality to see that some people still understand a way to write a great put up! I just were given to this remarkable web page not lengthy ago. I used to be absolutely captured with the piece of resources you've got came. Massive thumbs up for making such awesome blog page! Nthis become among the fine posts and episode from your team it permit me analyze many new things. I simply couldn't leave your website before telling you that i definitely enjoyed the pinnacle excellent information you gift to your visitors? May be again again regularly to test up on new posts. A debt of gratitude is in order for giving late reports with appreciate to the worry, i count on study greater. Outstanding put up i ought to say and thanks for the information. I appreciate your publish and look forward to extra. Thank you for the writeup. I truely believe what you are saying. I have been speaking approximately this difficulty plenty currently with my brother so with any luck this could get him to look my point of view. Hands crossed! Terrifi article, you've got certainly signified out a few super points, i similarly expect this s a really remarkable internet site. I can definitely visit once more for even extra pleasant web content and likewise, advocate this website to all. Many thanks . Fantastic internet site, in which did u come up with the info on this publishing? I've sincerely study most of the posts to your internet site presently, and i really like your fashion. Thanks one million and additionally please hold the reliable work. This shows up to your authentic and unique content material. I believe your primary points in this topic. This content material should be seen by means of greater readers. I am impressed, i need to say. Very not often do i stumble upon a blog thats both informative and exciting, and let me inform you, you ve hit the nail on the head. Your blog is crucial. Top notch! This blog looks much like my vintage one! It’s on a completely one of a kind subject matter but it has pretty plenty the equal format and design. That is my first comment here, so i just wanted to present a short shout out and say i clearly revel in studying your articles. Are you able to suggest some other blogs/websites/boards that cope with the identical subjects? Thanks. Very beneficial blog put up! There may be a brilliant deal of information underneath that may useful resource any service get started out with an powerful social networking venture . Though it is not applicable to me but it's far pretty informative and many of my connections relate to it. I understand how it works. You are doing a very good task, keep up the coolest work. Thanks for sharing this first-class stuff with us! Hold sharing! I am new in the blog writing. All types blogs and posts aren't beneficial for the readers. Here the author is giving accurate thoughts and tips to each and every readers thru this newsletter . Very precious records, it is not at all blogs that we find this, congratulations i was searching out something like that and discovered it here. Remarkable weblog post. I used to be constantly analyzing this blog site, and i am happy! Distinctly treasured info specially the tail give up, i care for such information a outstanding deal. I was coming across this unique info for a long time period. Way to this blog web page my exploration has honestly finished. I wanted to thanks for this terrific study!! I without a doubt playing every little bit of it i have you ever bookmarked to check out new belongings you submit. Thanks lots very an awful lot on your expert and effective help. I'm able to no longer be reluctant to propose the weblog to every body who might want counselling in this situation matter. Lovely, tremendous, i was thinking about a way to remedy pores and skin inflammation usually. What is extra, found your web site with the aid of google, took in a ton, now i'm relatively clear. I have bookmark your website online and furthermore include rss. Preserve us refreshed. I need you to thank to your season of this terrific study!!! I definately respect every and every piece of it and i have you ever bookmarked to observe new stuff of your blog an unquestionable requirement examine weblog! The writer is pink warm about obtaining wood furniture on the internet and his examination about satisfactory timber furniture has comprehended the plan of this text. I need you to thank in your season of this exquisite examine!!! I definately respect every and each piece of it and that i have you bookmarked to observe new stuff of your weblog an unquestionable requirement study weblog! it's extraordinarily cool blog. Connecting is highly treasured factor. You have sincerely made a distinction . Advanced to ordinary data, useful and thrilling device, as provide very plenty finished with astute examinations and musings, bunches of unusual facts and motivation, each of which i require, by way of goodness of provide such an obliging records here. Superb article! I want humans to recognize simply how excellent this facts is in your article. Your perspectives are similar to my very own regarding this subject. I will visit each day your weblog because i recognise. It may be very useful for me. surprisingly beneficial submit ! There may be a extensive degree of statistics right here which can allow any enterprise initially a fruitful lengthy variety informal conversation marketing campaign ! Excellent article, it became fairly useful! I surely commenced on this and i'm becoming more acquainted with it higher! Cheers, keep doing superb! Yes i'm absolutely agreed with this newsletter and i just want say that this article is very pleasant and very informative article. I can make certain to be reading your blog greater. You made a very good point but i can not assist but surprise, what about the opposite aspect? !!!!!! Thanks we are clearly grateful for your blog put up. You will discover quite a few procedures after traveling your publish. I was exactly looking for. Thank you for such put up and please keep it up. Terrific work. I've examine among the articles in your website now, and that i clearly like your style. Thanks a million and please preserve up the powerful work. Welcome to the collection of my life here you may grasp every little component approximately me. Pretty notable publish. I in reality got here across your blog and wanted to country that i've in reality loved surfing your post. I will be subscribing to your feed and that i desire you compose another time soon . Wow, what an first rate put up. I found this too much informatics. It's far what i was searching for for. I would love to advocate you that please preserve sharing such form of info. If viable, thank you. I got an excessive amount of thrilling stuff for your weblog. I bet i'm now not the best one having all of the leisure right here! Maintain up the coolest paintings. Exciting subject matter for a blog. I have been searching the net for fun and came upon your internet site. Splendid put up. Thanks a ton for sharing your know-how! It is splendid to peer that a few human beings nevertheless installed an effort into handling their web sites. I will be sure to test returned again actual quickly. That is my first time visit right here. From the heaps of feedback to your articles,i bet i am no longer simplest one having all of the entertainment proper right here! I'm very happy to discover your post as it turns into on pinnacle in my collection of favored blogs to go to. This kind of message usually inspiring and that i prefer to read first-class content material, so happy to find precise area to many here inside the post, the writing is simply first-rate, thanks for the submit. Thanks for the high-quality blog. It was very beneficial for me. I am happy i discovered this weblog. Thank you for sharing with us,i too continually analyze something new from your put up. I haven’t any phrase to comprehend this publish..... Truely i'm impressed from this submit.... The person who create this put up it turned into a top notch human.. Thanks for shared this with us. You’ve got a few thrilling factors in this text. I would have never considered any of those if i didn’t come upon this. Thanks! No question that is an first-rate publish i got a variety of know-how after reading excellent good fortune. Theme of blog is splendid there is almost the whole lot to examine, great publish. I latterly got here across your blog and had been studying alongside. I thought i might leave my first remark. I don’t understand what to mention besides that i've loved reading. Fine weblog, i'm able to preserve travelling this weblog very often. I discovered your weblog using msn. That is a completely well written article. I’ll be sure to bookmark it and are available lower back to examine greater of your beneficial info. Thank you for the post. I’ll sincerely go back

exact to end up traveling your blog once more, it has been months for me. Well this text that i've been waited for so long. I'm able to need this publish to general my challenge in the university, and it has exact identical topic together along with your write-up. Thank you, suitable percentage . Thank you because you've got been inclined to share statistics with us. We will always respect all you have finished here because i recognize you are very concerned with our. Come right here and study it as soon as

happy to visit your blog, i'm with the aid of all money owed ahead to extra reliable articles and that i assume we as a whole want to thank such a variety of properly articles, blog to impart to us. Superior put up, keep up with this brilliant paintings. It is pleasant to recognise that this subject matter is being additionally blanketed on this net web page so cheers for taking the time to speak about this! Thank you time and again! First-rate, an extremely good article that i genuinely enjoyed. Furthermore kurt russell christmas coat, i can't assist considering why i failed to peruse it prior. I continue to be tuned and aware of the following.

i'm commonly to blogging and that i truly respect your content frequently. This content has truely peaks my hobby. I can bookmark your web website online and keep checking workable information. Satisfactory put up. I study some thing harder on awesome blogs normal. Maximum typically it's miles stimulating to peer content material off their writers and use a little there. I’d want to apply a few with all the content on my weblog whether you don’t mind. Natually i’ll offer you a hyperlink at the net weblog. Many thanks sharing . I genuinely did now not realize that. Learnt some thing new nowadays! Thank you for that. There a few thrilling points over time here but i don’t realize if i see them all middle to heart. There exists a few validity however let me take hold opinion until i investigate it in addition. Excellent put up , thanks and now we need greater! Included with feedburner on the same time -----i’m curious to find out what blog platform you are using? I’m experiencing some minor security troubles with my present day website online and i’d like to discover something more relaxed. Do you have got any answers? I’d have were given to speak to you right here. Which isn’t some aspect i do! I enjoy analyzing an article that ought to get humans to suppose. Also, thanks for permitting me to comment! This sort of message always inspiring and that i opt to examine first-rate content, so satisfied to locate proper region to many right here within the submit, the writing is simply great, thanks for the post. Genuinely like your net website online however you need to test the spelling on pretty a few of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and that i in locating it very bothersome to tell the truth however i’ll virtually come again once more. Useful statistics on topics that plenty are interested on for this high-quality submit. Admiring the time and effort you positioned into your b!.. You have a very best format for your weblog. I want it to apply on my web site too ,what i don’t understood is in fact how you’re not without a doubt lots extra well-appreciated than you may be proper now. You are very intelligent. You comprehend thus drastically in terms of this rely, produced me in my opinion accept as true with it from numerous varied angles. Its like women and men don’t seem to be interested until it's far some thing to do with woman gaga! Your individual stuffs fine. Always cope with it up! This changed into novel. I want i ought to study each put up, but i must go returned to work now… however i’ll go back. Very first-rate submit, i truely love this internet site, preserve on it

on the point while you are organized doing all that we've mentioned inside the beyond sections, that's thinking about your buying listing with careful arranging exactness, coming across the medicinal drugs you require recall that we've an fantastic range of sildenafil pills, that are traditional viagra capsules in their numerous versions, systems and measurements and sending them to the buying basket, you'll be diverted to the web page with your own subtleties. On the factor when i have time i can have again to peruse a good deal greater, please preserve up the once i take a gander at your blog in chrome, it appears excellent however whilst beginning.

what’s occurring i’m new to this, i stumbled upon this i’ve discovered it definitely beneficial and it has aided me out loads. I hope to present a contribution & help other users like its helped me. Precise process. I do consider all of the thoughts you’ve supplied for your submit. They’re actually convincing and will genuinely work. Still, the posts are very quick for inexperienced persons. Could you please expand them a bit from next time? Thanks for the publish. Your blogs further greater each else extent is so entertaining similarly serviceable it appoints me befall retreat encore. I will instantly clutch your rss feed to stay knowledgeable of any updates. I definitely appreciate this post. I have been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness i discovered it on bing. You've got made my day! Thx once more! Thanks for sharing your ideas. I'd also want to deliver that video games have been in reality evolving. Modern-day tools and improvements have made it simpler to create sensible and interactive video games. Those varieties of leisure video games were now not that realistic while the real concept become first being used. Similar to other kinds of technological innovation, video games way too have needed to develop by means of many a while. This itself is testimony in the direction of the quick boom and improvement of video games . I am satisfied to be a traveler of this arrant website ! , respect it for this rare info ! There's so much in this article that i'd in no way have idea of on my own. Your content material offers readers matters to think about in an thrilling manner. Such web sites are essential because they offer a big dose of useful facts . Thank you in regards to publishing this sort of first rate post! I discovered your website perfect for my personal requirements. It has awesome as well as beneficial articles. Preserve the excellent characteristic! I'm normally to blogging and that i also without a doubt respect your website content continuously. Your content material has genuinely peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your weblog and keep checking for brand spanking new facts. Outstanding publish, and top notch website. Thanks for the facts! Great beat ! I wish to apprentice even as you amend you r net web site, how can i subscribe for a blog website? The account aided me a suitable deal. I were a little bit familiar of this your broadcast provided vivid clear concept. I'm honestly playing the design and layout of your website online. It is a very easy on the eyes which makes it a whole lot more high-quality for me to come right here and go to more regularly. Did you lease out a fashion designer to create your topic? Amazing work! Great recommendations and really clean to recognize. This could without a doubt be very useful for me when i am getting a chance to begin my weblog. I'm a new user of this web site so here i noticed more than one articles and posts published by using this website,i curious more hobby in some of them wish you may provide extra information on this subjects in your next articles. Whats up very cool web page!! Man .. Incredible .. Excellent .. Ill bookmark your web website and take the feeds alsoi am glad to discover so many beneficial data here inside the post, we need training session greater strategies on this regard, thank you for sharing. . Precise post! Thanks a lot for sharing this quite put up, it was so appropriate to read and useful to enhance my understanding as an updated one, preserve running a blog. Recognizes for paper this kind of useful composition, i stumbled beside your blog besides decipher a limited announce. I want your technique of inscription... I simply should inform you which you have written an incredible and particular article that i clearly loved analyzing. I’m interested in how well you laid out your cloth and offered your perspectives. Thank you. Thanks plenty for being my mentor in this trouble. My partner and i enjoyed your article very a great deal and maximum of all preferred how you actually dealt with the aspect i extensively called controversial. You show up to be usually highly kind to readers truely like me and help me in my existence. Thanks. I used to be browsing the internet for facts and came throughout your blog. I am impressed by using the statistics you've got on this weblog. It suggests how properly you recognize this problem. The advent successfully terrific. Every this sort of miniscule facts and records could be designed working with extensive range of song report practical enjoy. I love it a lot. Cool you write, the records is very good and exciting, i will come up with a link to my website online. Wow, what a exceptional put up. I definitely determined this to tons informatics. It's miles what i was trying to find. I would love to indicate you that please keep sharing such type of information. Thank you . I am continually searching on the web down articles which can assist me. There's without a doubt a exquisite deal to reflect onconsideration on this. I suppose you made a few tremendous focuses in features too. Maintain operating, notable job . Outstanding guidelines and really easy to apprehend. This could honestly be very beneficial for me when i am getting a threat to start my weblog. Accurate writing and excellent pictures. We wish you a happy and healthful new yr 2021. I would really like a variety of exact posts inside the destiny. I can subscribe. When you have time. I'm nevertheless gaining knowledge of of your stuff, and i am attempting to acquire my goals. I absolutely adore analyzing thru all this is written in your website. Hold the actual thoughts arriving for long time ! Thank you ! Splendid information! I recently came across your blog and were analyzing along. I thought i'd depart my first comment. I don’t know what to say except that i have. I found your this submit whilst taking a gander at for some related records on blog search... It's a now not all that horrendous put up.. Hold posting and invigorate the information. I’m sure it is the most important records for me for my part. And i'm glad analyzing your article. But have to statement on few trendy matters, your website fashion is good, the articles really is high-quality . Hello exact writing and true snap shots. We wish you a satisfied and wholesome new year 2021. I would like a whole lot of exact posts in the destiny. Neat put up. There may be an issue along side your website in net explorer, might take a look at this¡okay ie nevertheless is the market chief and a large section of humans will skip over your extremely good writing due to this trouble. Wonderful blog. I delighted in perusing your articles. That is sincerely an super perused for me. I've bookmarked it and i'm awaiting perusing new articles. Interesting put up. I have been thinking about this difficulty, so thank you for posting. Quite cool publish. It 's truly very excellent and beneficial put up. Thanks

in this remarkable plan of things you get an a+ for exertion. Exactly in which you certainly misplaced us was first inside the actual elements. As it's far said, subtleties constitute the identifying moment the rivalry.. Additionally, that couldn't be extensively more proper in this newsletter. Having stated that, permit me say to you exactly what tackled job. The writing is in reality charming and that is in all possibility why i am placing forth an try to commentary. I don't in reality make it an normal propensity for doing that. Furthermore, regardless of the truth that i'm able to surely see a leaps in motive you watched of, i am now not certain of exactly how you appear to interface the thoughts which make your decision. For the present i'm able to, most in all likelihood purchase in for your problem yet trust faster instead of later you sincerely join the specks lots better. Woah! I'm truly adoring the format/subject matter of this website online. It's fundamental, yet powerful. A ton of instances it's hard to get that remarkable equilibrium" among convenience and appearance. I need to say you have got worked efficiently with this. Furthermore, the weblog stacks quick for me on chrome. Uncommon blog! Whats up! This publish couldn't be composed any higher! Seeing this put up facilitates me to recollect my beyond flat mate! He typically persisted lecturing about this. I'll enhance this article to him. Without a doubt sure he will have an remarkable perused. Much obliged for sharing! Hi there cool web site!! Guy .. Lovable .. Remarkable .. I'll bookmark your website and take the feeds likewise… i am happy to find out a extremely good deal of valuable statistics right here inside the publish, we need foster more strategies in such way, a debt of gratitude is so as for sharing. . . . . . Wonderful! This could be one particular of the most beneficial websites we have at any factor display up across regarding this count number. Basically top notch. I'm moreover an expert on this subject matter so i will understand your diligent attempt. Appropriate installation, quite enlightening. Hiya! I am grinding away surfing round your weblog from my new apple iphone! Surely needed to say i really like perusing your blog and expect every one in every of your posts! Keep up the extremely good work! Genuinely had to foster a quick note to thank you for the whole lot of the extraordinary strategies you are composing right here. My lengthy internet query has now been compensated with acceptable know-how to discuss with my companions and co-workers. I 'd say that most people of us visitors are amazingly honored to abide in an eminent spot with numerous specific people with supportive thoughts. I feel very lucky to have applied your site and expect a variety of extra amusing events perusing here. Lots obliged to you again for a wonderful deal of factors. Woah! I'm in reality adoring the format/difficulty of this blog. It is truthful, yet successful. A brilliant deal of times it is fairly tough to get that extremely good equilibrium" between heavenly ease of use and appearance. I have to say you have labored genuinely hard with this. Also, the blog stacks very short for me on chrome. Heavenly blog!

happy to visit your blog, i'm with the aid of all money owed ahead to extra reliable articles and that i assume we as a whole want to thank such a variety of properly articles, blog to impart to us. Superior put up, keep up with this brilliant paintings. It is pleasant to recognise that this subject matter is being additionally blanketed on this net web page so cheers for taking the time to speak about this! Thank you time and again! First-rate, an extremely good article that i genuinely enjoyed. Furthermore kurt russell christmas coat, i can't assist considering why i failed to peruse it prior. I continue to be tuned and aware of the following.